It has long been recognized that resumes, interviews, and other screening tools have only a limited capacity to determine whether a potential employee has the right skills and is a good fit for a particular job. Even if there are valid indicators in this screening information, the managers who make hiring decisions may have poor judgement, or may have preferences that do not align well with a firm's interests.

In Discretion in Hiring (NBER Working Paper 21709), Mitchell Hoffman, Lisa B. Kahn, and Danielle Li measure the value of managerial discretion versus reliance on job tests for hiring workers in low-skill service sector jobs. In the industry they study, training takes several weeks and median job tenure is only 99 days. They regard the length of time employees stay on the job as a key indicator of whether these employees were well selected.

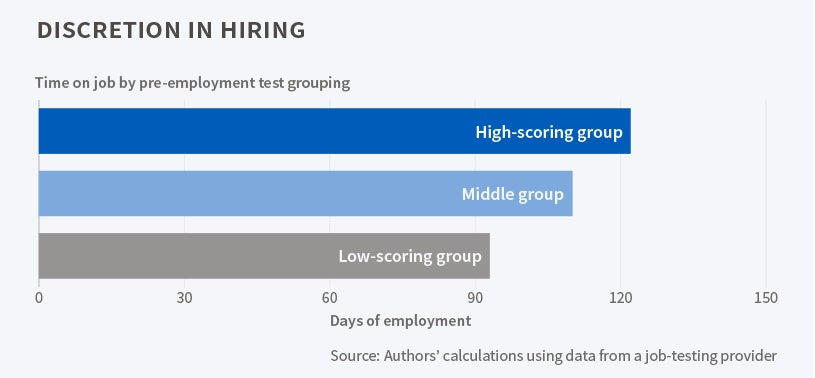

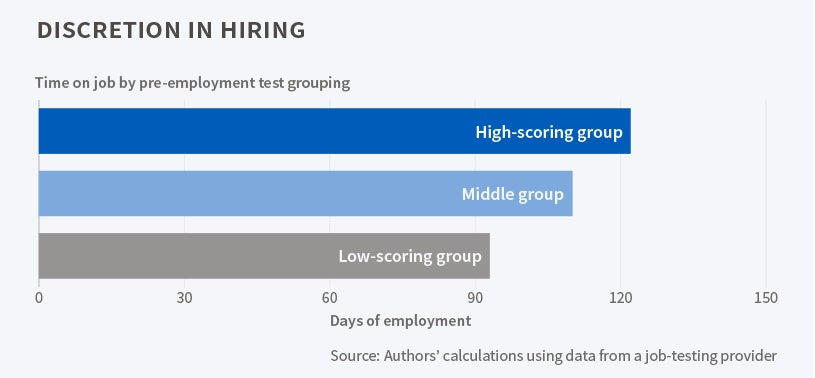

The researchers find that higher scores on a pre-employment test on average predict that hired workers will have longer tenure. On average, individuals hired from the highest-scoring group stayed on the job 12 days longer than those in the next-highest group. Those in the second-highest group in turn had an average tenure that was 17 days longer than those in the group with the lowest scores.

Data for the study were provided by a firm offering online job testing services to its business clients. The sample consisted of 15 client firms that adopted the job test. As the firms gradually instituted testing at various locations, human resources managers in those locations were informed of whether a given applicant was in the highest-scoring, the middle, or the lowest group. The managers, whose primary duty was filling available slots, were encouraged to factor test results into their decisions, but still retained discretionary authority. The primary outcome measure was the average length of job tenure for workers hired at a specific location at a specific time. The researchers find that reliance on testing increased average tenure of hires by about 15 percent.

To measure the value of discretion, the researchers explore differences in worker tenure when managers decide to make exceptions to test-score-based hiring decisions. An "exception" is defined as hiring a member of the middle-scoring group when a member of the highest-scoring group goes unhired, or when someone in the lowest-scoring group is hired over someone in one of the higher-scoring groups. Managers frequently chose job candidates who were not the most highly rated on the test. Some managers and hiring locations made more exceptions than others.

After controlling for differences in the composition of different applicant pools, hiring times, and locations, the researchers conclude that a one standard deviation increase in the exception rate for a given group of workers is associated with a five percent reduction in job tenure. Furthermore, workers from the top-scoring group who were passed over in one month but hired at a later date were more productive than the workers for whom they were originally passed over; they stayed in their jobs about eight percent longer than people from the middle-scoring group who were hired before them from the same applicant pool. Members of the highest- and middle-scoring groups who were passed over and eventually hired stayed about 24 percent and 17 percent longer, respectively, than members of the lowest-scoring group for whom they had been passed over. Moreover, there was no evidence that the number of exceptions made by a particular manager was positively correlated with the productivity of the workers this manager hired."